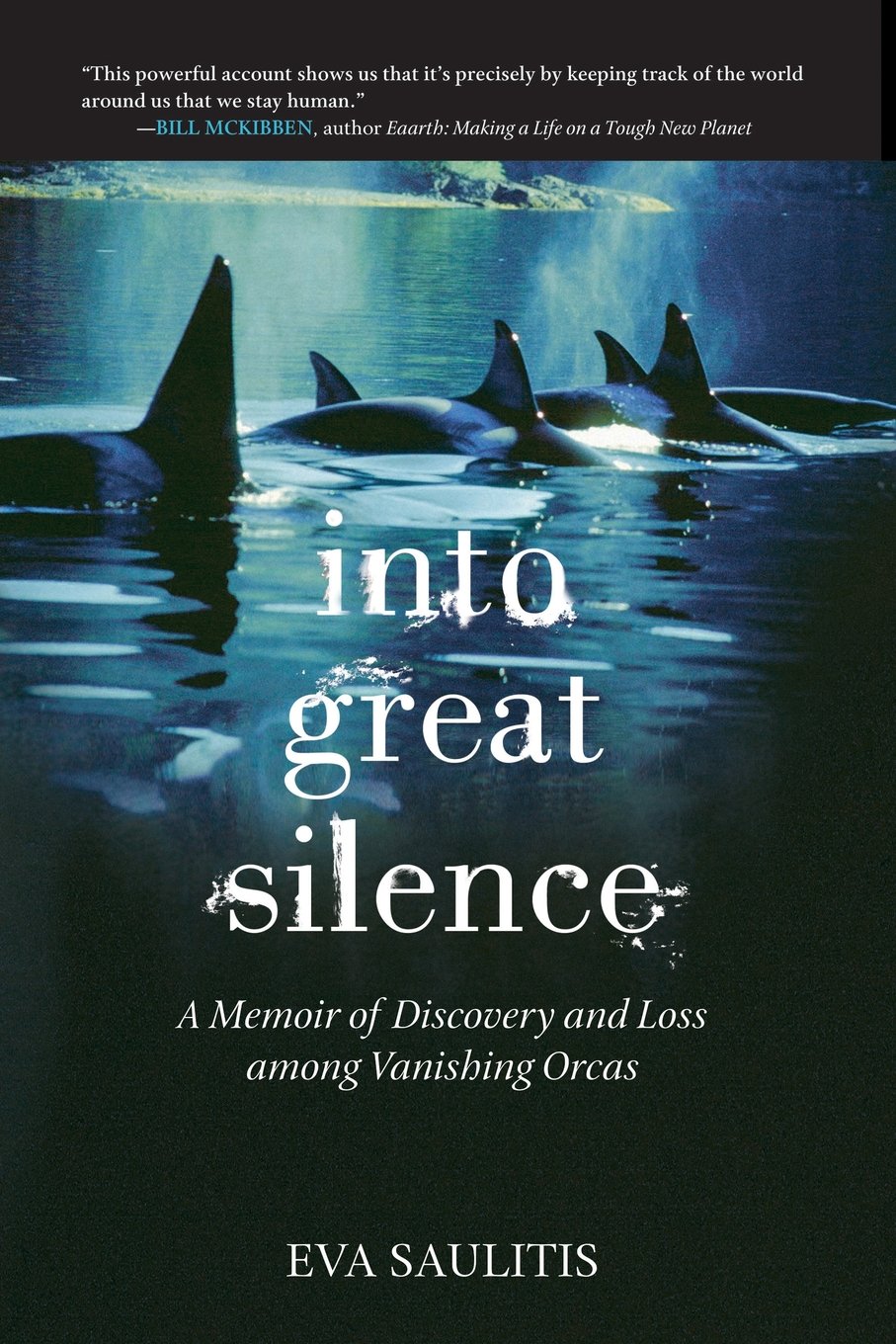

Extinction is forever. Every time I mull over this thought, it brings into focus for me, more than ever, of our responsibilities as a species, of the succinct realization of our inter-relatedness and common fate with all other life forms inhabiting our shared ecosystem. My interest in orcas (Orcinus orca) go back a long time, lapping up accounts of their inherently amiable, extremely social disposition, swimming the oceans in tightly knit mother-centred families and extended families or pods, as they are called. Never had the good fortune of encountering one in person, but the closest I got was through the writings of marine biologist Eva Saulitis who spent long years intimately observing and comprehending the lives of a tiny, threatened orca population in the waters of a scenic inlet known as Prince William Sound in the Gulf of Alaska, Alaska, USA. Among other marine life forms in Prince Wiliam Sound, Saulitis spent the most time studying a genetically distinct orca ecotype known as the AT1 or ‘Chugach’ transients (transients being mammal eaters.)

Six of the transient orcas in Prince William Sound. Photograph by Eva Saulitis.

AT1 transient family tree, courtesy Carey Restino.

This small group of orcas comprising of 22 individuals, was censused for the first time in 1984 and by the summer of 2010, this population dwindled to the last 7 sighted individuals, and no new calves were born. An already tiny population of unique orcas brought to the edge by no other reason other than deeply unfortunate, and possibly avoidable human caused mortality, in the form of the devastating Exxon Valdez oil spill in the pristine waters of Prince William Sound. As of January 2016, after three decades of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the numerous litigation draw to a close, and the economic damage in dollars and cents have been doing the rounds for years. But the truth is, one can never calculate the true, far reaching, infinite damage brought about by oil spills such as these, for they mercilessly wipe out generations of interdependent life-forms, marine, non-marine. One can never ‘clean up’ oil spills, for there is so much blood in our human hands, in our fossil fuel dependent ways of life.

Exxon Valdez spill affected area, courtesy Conservation GIS Center, Alaska.

Saulitis is probably one of the few long term ‘eye-witnesses’ to the brutal devastation brought about by the oil spill, of the thousands of carcasses, of seabirds, otters, seals, eagles, salmons, herrings, to the disappearance of the distinct, social individuals of the tiny orca pod she grew to love and respect. What is important to understand about orcas and their social lives, is that they are active ‘vocal’ communicators, which each orca pod communicating in their own vocal repertoire and acoustic behavior or developing ‘dialects’ of their own which act like social glue and bring in community harmony. Each pod dialect is unique to their own kind, which means, one orca pod cannot fully understand the vocalizations and acoustic behaviour of another orca pod, probably fairly similar to human puzzlement in hearing another language. I imagine a time when the last surviving orca of Prince William Sound, swimming alone in the bleak, unforgiving waters (that were once home and family), and vocalizing a hopeful pulsed call, a lone cry, only to realize, that there is no one around, anymore. That call will go unanswered, forever.

A lone orca in Prince William Sound. Photograph by Don Bain.

A glimpse of orcas in the wild.

Vocal repertoire and acoustic behavior of orcas.

Further reading: AT1 transient orcas, Exxon Valdez accident, Oil spill Q&A.

veryveryinterestingwebsite.have been visiting! thankyou!

veryveryinterestingwebsite.have been visiting! thankyou! Photo gallery

Photo gallery With all the magical places you are checking off your bucket list! I want to know how to be you :)

With all the magical places you are checking off your bucket list! I want to know how to be you :) Happy teachers day! Out of all, your teachings n your way of being have really made a big positive impact on me.

Happy teachers day! Out of all, your teachings n your way of being have really made a big positive impact on me. Photo gallery

Photo gallery Milindo Taid – ace teacher, rockstar guide to my projects at film school, guitarist and photographer too. Really good human being as well

Milindo Taid – ace teacher, rockstar guide to my projects at film school, guitarist and photographer too. Really good human being as well You’re a role model sir, such awesomeness !!! :D

You’re a role model sir, such awesomeness !!! :D You are inimitable!

You are inimitable! Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Hi Milindo, hope you are inspiring many more around you…wherever you are!

Hi Milindo, hope you are inspiring many more around you…wherever you are! Photo gallery

Photo gallery So glad you enjoyed my photos, really honored to be featured on your blog. thank you sir!

So glad you enjoyed my photos, really honored to be featured on your blog. thank you sir! Its really good to see you Milindo, with such awesome stuff from you as usual.. loved your blog as well!

Its really good to see you Milindo, with such awesome stuff from you as usual.. loved your blog as well! i really like your blog – good interesting stuff as always !

i really like your blog – good interesting stuff as always ! Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery We need more teachers like you :)

We need more teachers like you :) Your courses were always the best. By the way, just went through a bit of your website. It’s great! Some good stuff in there that I wouldn’t normally chance upon

Your courses were always the best. By the way, just went through a bit of your website. It’s great! Some good stuff in there that I wouldn’t normally chance upon You are awesome :)

You are awesome :) Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery OMG its like a painting!! you have taken photography to another level!!!

OMG its like a painting!! you have taken photography to another level!!! love ur pics…they are like those moments which u capture in your mind and wished u had a camera right at that moment to capture it…but u actually do capture them :) beautiful…!!!

love ur pics…they are like those moments which u capture in your mind and wished u had a camera right at that moment to capture it…but u actually do capture them :) beautiful…!!! Photo gallery

Photo gallery Oldest operating bookstore

Oldest operating bookstore Never thought I’d say this, but it was the most interesting classes I’ve sat in.. and of course, the day you played Sultans of Swing for us. Hope you continue to influence the next generations with your dynamic yet simple teachings.

Never thought I’d say this, but it was the most interesting classes I’ve sat in.. and of course, the day you played Sultans of Swing for us. Hope you continue to influence the next generations with your dynamic yet simple teachings. Your website is full of delightful posts. I’m going to have to watch where my time goes when I’m visiting! :)

Your website is full of delightful posts. I’m going to have to watch where my time goes when I’m visiting! :) Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery This is by far amongst the best curated creative content sites out there and the eye and vision of one man, when good, works better than any funded team. Inspired enormously once again :)

This is by far amongst the best curated creative content sites out there and the eye and vision of one man, when good, works better than any funded team. Inspired enormously once again :) hope you’re changing the world as always :)

hope you’re changing the world as always :) Guitar in your hand reminds me of the MCRC days! You are terrific… :)

Guitar in your hand reminds me of the MCRC days! You are terrific… :) Grt milindo. eachtime want to check out something good on net…know where to go now!

Grt milindo. eachtime want to check out something good on net…know where to go now! Just detected your blog: impressive. wishing you continued inspiration and health.

Just detected your blog: impressive. wishing you continued inspiration and health. Milind never told u but u were my first true inspiration….I almost learnt the guitar watching u play…..thanx for being there

Milind never told u but u were my first true inspiration….I almost learnt the guitar watching u play…..thanx for being there Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery #NowFollowing @Milindo_Taid One of the most influential n interesting mentor from my design school. Always loaded. :)

#NowFollowing @Milindo_Taid One of the most influential n interesting mentor from my design school. Always loaded. :) Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery great blog :)

great blog :) You are the only faculty member I could connect to!

You are the only faculty member I could connect to! I was just looking at your website… amazing it is… full of knowledge as always..

I was just looking at your website… amazing it is… full of knowledge as always.. Love your site Milindo. I was excited to see you displaying my husband’s watermelon carvings

Love your site Milindo. I was excited to see you displaying my husband’s watermelon carvings Still a fan of your unique and sweet finger strum on acoustic guitar. It made an ordinary guitar sound great. Would just love to see and hear one of those too.

Still a fan of your unique and sweet finger strum on acoustic guitar. It made an ordinary guitar sound great. Would just love to see and hear one of those too. Photo gallery

Photo gallery You’ll love this site by the awesome Milindo Taid

You’ll love this site by the awesome Milindo Taid I discover TL of a writer and respected intellectual, with a tolerant, global conscience: @GhoshAmitav – tx @Milindo_Taid

I discover TL of a writer and respected intellectual, with a tolerant, global conscience: @GhoshAmitav – tx @Milindo_Taid Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Absolutely amazing blog – a chest full of treasure.

Absolutely amazing blog – a chest full of treasure. Photo gallery

Photo gallery