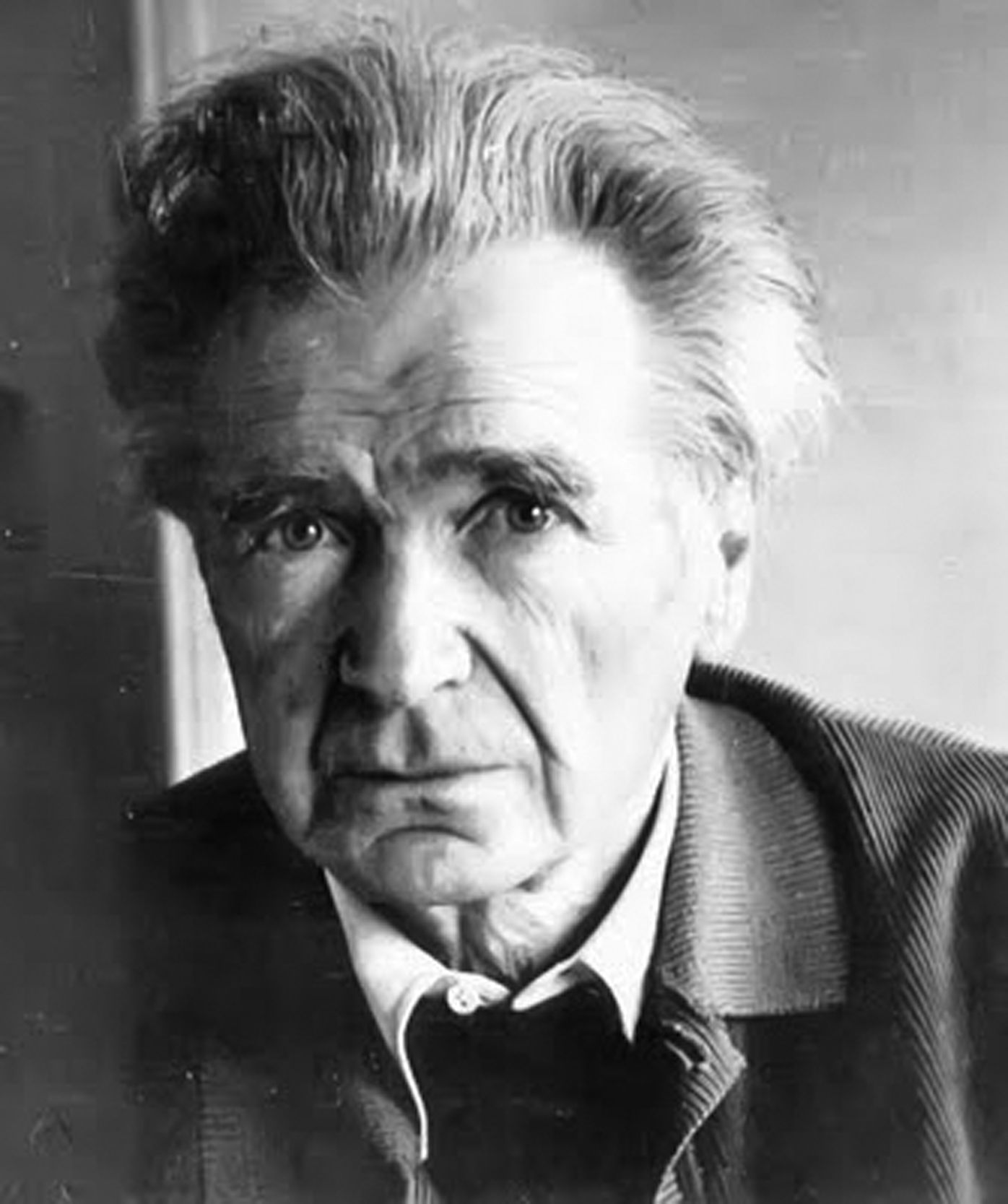

Emil Cioran: Nihilism as affirmation in the face of inevitable Annihilation

My first brush with the relentlessly dark and bleak vision of Romananian writer-philospher Emil Cioran came by way of the pages of the fascinating ‘A Short History of Decay‘(tr.), his first publication written in French, an outcome of the churning of many a long year. Cioran’s philosophical stance (although he probably would have balked at such an assumption) is to be able to embrace all that has been made taboo by occidental civilizations’ zealous championship of the pursuit of happiness as one of the vital life goals. Pessimism and cynicism and other such realist impulses have curiously been shrouded with a range of negative connotations, for, the pursuit of happiness is such a powerfully embedded psycho-socio-cultural construct. In all of this, Cioran is pretty much the elevated insomniac, a traverser between dawn and dusk, good and evil, despair and ecstasy – his remarkably astute, often dark wit laced writing conjures reality without any foundation and mascara, scars are made visible, and in the best of traditions of negation and nihilism, his body of work is a slap of awakening for all conscientious humans struggling to come to terms with the brutality of everyday existence. Read More…

i really like your blog – good interesting stuff as always !

i really like your blog – good interesting stuff as always ! Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery great blog :)

great blog :) Oldest operating bookstore

Oldest operating bookstore You’re a role model sir, such awesomeness !!! :D

You’re a role model sir, such awesomeness !!! :D Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery Your website is full of delightful posts. I’m going to have to watch where my time goes when I’m visiting! :)

Your website is full of delightful posts. I’m going to have to watch where my time goes when I’m visiting! :) Guitar in your hand reminds me of the MCRC days! You are terrific… :)

Guitar in your hand reminds me of the MCRC days! You are terrific… :) Photo gallery

Photo gallery So glad you enjoyed my photos, really honored to be featured on your blog. thank you sir!

So glad you enjoyed my photos, really honored to be featured on your blog. thank you sir! Photo gallery

Photo gallery With all the magical places you are checking off your bucket list! I want to know how to be you :)

With all the magical places you are checking off your bucket list! I want to know how to be you :) veryveryinterestingwebsite.have been visiting! thankyou!

veryveryinterestingwebsite.have been visiting! thankyou! Absolutely amazing blog – a chest full of treasure.

Absolutely amazing blog – a chest full of treasure. Your courses were always the best. By the way, just went through a bit of your website. It’s great! Some good stuff in there that I wouldn’t normally chance upon

Your courses were always the best. By the way, just went through a bit of your website. It’s great! Some good stuff in there that I wouldn’t normally chance upon Photo gallery

Photo gallery Grt milindo. eachtime want to check out something good on net…know where to go now!

Grt milindo. eachtime want to check out something good on net…know where to go now! This is by far amongst the best curated creative content sites out there and the eye and vision of one man, when good, works better than any funded team. Inspired enormously once again :)

This is by far amongst the best curated creative content sites out there and the eye and vision of one man, when good, works better than any funded team. Inspired enormously once again :) I was just looking at your website… amazing it is… full of knowledge as always..

I was just looking at your website… amazing it is… full of knowledge as always.. Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery We need more teachers like you :)

We need more teachers like you :) Hi Milindo, hope you are inspiring many more around you…wherever you are!

Hi Milindo, hope you are inspiring many more around you…wherever you are! Love your site Milindo. I was excited to see you displaying my husband’s watermelon carvings

Love your site Milindo. I was excited to see you displaying my husband’s watermelon carvings Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Still a fan of your unique and sweet finger strum on acoustic guitar. It made an ordinary guitar sound great. Would just love to see and hear one of those too.

Still a fan of your unique and sweet finger strum on acoustic guitar. It made an ordinary guitar sound great. Would just love to see and hear one of those too. Photo gallery

Photo gallery I discover TL of a writer and respected intellectual, with a tolerant, global conscience: @GhoshAmitav – tx @Milindo_Taid

I discover TL of a writer and respected intellectual, with a tolerant, global conscience: @GhoshAmitav – tx @Milindo_Taid Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery You’ll love this site by the awesome Milindo Taid

You’ll love this site by the awesome Milindo Taid love ur pics…they are like those moments which u capture in your mind and wished u had a camera right at that moment to capture it…but u actually do capture them :) beautiful…!!!

love ur pics…they are like those moments which u capture in your mind and wished u had a camera right at that moment to capture it…but u actually do capture them :) beautiful…!!! Utterly Brilliant! I just thought you should know that you have engaged another human with your work here, and for that I thank you!

Utterly Brilliant! I just thought you should know that you have engaged another human with your work here, and for that I thank you! You are inimitable!

You are inimitable! #NowFollowing @Milindo_Taid One of the most influential n interesting mentor from my design school. Always loaded. :)

#NowFollowing @Milindo_Taid One of the most influential n interesting mentor from my design school. Always loaded. :) Milind never told u but u were my first true inspiration….I almost learnt the guitar watching u play…..thanx for being there

Milind never told u but u were my first true inspiration….I almost learnt the guitar watching u play…..thanx for being there hope you’re changing the world as always :)

hope you’re changing the world as always :) Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery Never thought I’d say this, but it was the most interesting classes I’ve sat in.. and of course, the day you played Sultans of Swing for us. Hope you continue to influence the next generations with your dynamic yet simple teachings.

Never thought I’d say this, but it was the most interesting classes I’ve sat in.. and of course, the day you played Sultans of Swing for us. Hope you continue to influence the next generations with your dynamic yet simple teachings. Its really good to see you Milindo, with such awesome stuff from you as usual.. loved your blog as well!

Its really good to see you Milindo, with such awesome stuff from you as usual.. loved your blog as well! Photo gallery

Photo gallery OMG its like a painting!! you have taken photography to another level!!!

OMG its like a painting!! you have taken photography to another level!!! Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery You are the only faculty member I could connect to!

You are the only faculty member I could connect to! Just detected your blog: impressive. wishing you continued inspiration and health.

Just detected your blog: impressive. wishing you continued inspiration and health. Milindo Taid – ace teacher, rockstar guide to my projects at film school, guitarist and photographer too. Really good human being as well

Milindo Taid – ace teacher, rockstar guide to my projects at film school, guitarist and photographer too. Really good human being as well Photo gallery

Photo gallery