Edmund Husserl: Cogitations on First Philosophy

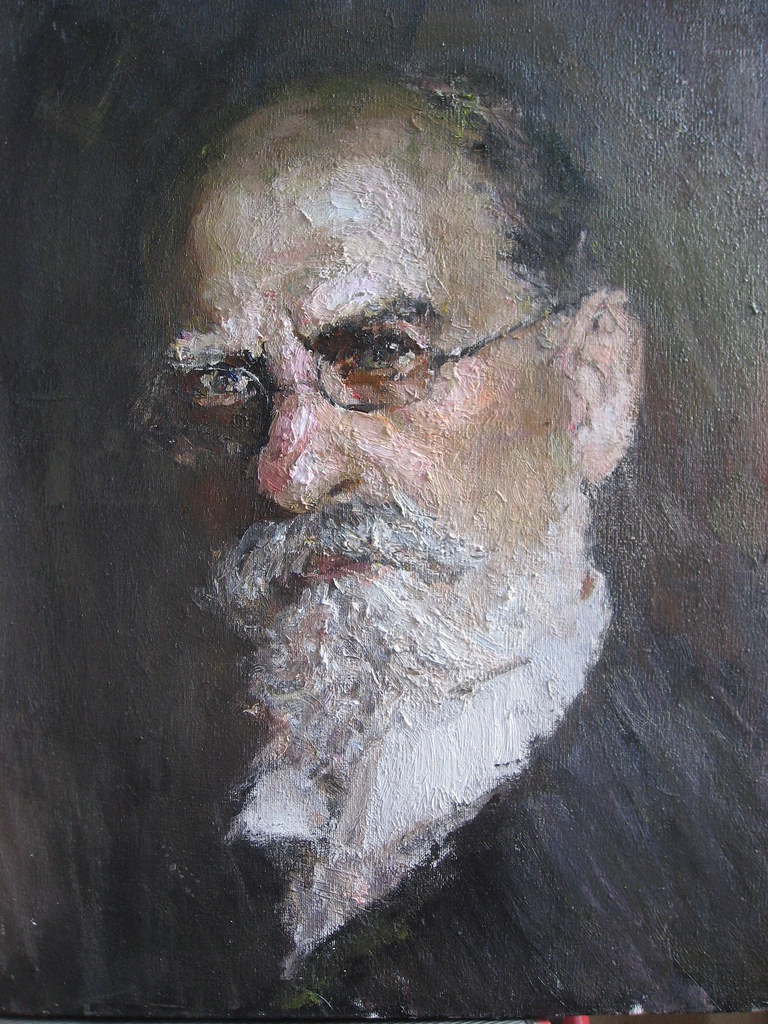

Moravia born philosopher Edmund Husserl spent his life teaching in German universities, and during the course of his intellectual life, he came to be regarded as the leading and influential figure in phenomenology (which took two successive forms in his own work, descriptive and transcendental). In this Husserl Memorial Lecture from 2009, Prof. Robert Sokolowski speaks on “Husserl on First Philosophy”, where, he argues that in this day and age, Husserl offers the possibility of a return to first philosophy. In Aristotle, first philosophy is defined as the theorizing of being as being. It is also called metaphysics, even though it was not given that name by Aristotle himself. The book in which Aristotle carries out this first philosophy was was entitled ‘ta meta ta physika’ by its editors. They called it the study of issues that are “beyond’the physical things. The study of separate entities comprises only a small part of Aristotle’s ‘Metaphysics’. His first philosophy spends most of its time examining things like prediction, truth, falsity, contradiction, substances and accidents, definition, form and substrate, and the potential and the actual. Metaphysics theorizes truth. Beyond the physicals – “meta ta physika”. Logic, truth, contradiction and predication, belong to being as being, and not being as material. Aristotle turns to the examination of being as being, which is also what Husserl does. Husserl’s phenomenology can be defined as the study of intellect as intellect, mind as mind, reason as reason.

.jpg)

veryveryinterestingwebsite.have been visiting! thankyou!

veryveryinterestingwebsite.have been visiting! thankyou! You are awesome :)

You are awesome :) Still a fan of your unique and sweet finger strum on acoustic guitar. It made an ordinary guitar sound great. Would just love to see and hear one of those too.

Still a fan of your unique and sweet finger strum on acoustic guitar. It made an ordinary guitar sound great. Would just love to see and hear one of those too. Happy teachers day! Out of all, your teachings n your way of being have really made a big positive impact on me.

Happy teachers day! Out of all, your teachings n your way of being have really made a big positive impact on me. Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery hope you’re changing the world as always :)

hope you’re changing the world as always :) You’ll love this site by the awesome Milindo Taid

You’ll love this site by the awesome Milindo Taid So glad you enjoyed my photos, really honored to be featured on your blog. thank you sir!

So glad you enjoyed my photos, really honored to be featured on your blog. thank you sir! Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery You’re a role model sir, such awesomeness !!! :D

You’re a role model sir, such awesomeness !!! :D Oldest operating bookstore

Oldest operating bookstore Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery With all the magical places you are checking off your bucket list! I want to know how to be you :)

With all the magical places you are checking off your bucket list! I want to know how to be you :) Your website is full of delightful posts. I’m going to have to watch where my time goes when I’m visiting! :)

Your website is full of delightful posts. I’m going to have to watch where my time goes when I’m visiting! :) Hi Milindo, hope you are inspiring many more around you…wherever you are!

Hi Milindo, hope you are inspiring many more around you…wherever you are! You are the only faculty member I could connect to!

You are the only faculty member I could connect to! Photo gallery

Photo gallery Never thought I’d say this, but it was the most interesting classes I’ve sat in.. and of course, the day you played Sultans of Swing for us. Hope you continue to influence the next generations with your dynamic yet simple teachings.

Never thought I’d say this, but it was the most interesting classes I’ve sat in.. and of course, the day you played Sultans of Swing for us. Hope you continue to influence the next generations with your dynamic yet simple teachings. Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Love your site Milindo. I was excited to see you displaying my husband’s watermelon carvings

Love your site Milindo. I was excited to see you displaying my husband’s watermelon carvings Photo gallery

Photo gallery Absolutely amazing blog – a chest full of treasure.

Absolutely amazing blog – a chest full of treasure. I was just looking at your website… amazing it is… full of knowledge as always..

I was just looking at your website… amazing it is… full of knowledge as always.. Milind never told u but u were my first true inspiration….I almost learnt the guitar watching u play…..thanx for being there

Milind never told u but u were my first true inspiration….I almost learnt the guitar watching u play…..thanx for being there Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Photo gallery

Photo gallery Milindo Taid – ace teacher, rockstar guide to my projects at film school, guitarist and photographer too. Really good human being as well

Milindo Taid – ace teacher, rockstar guide to my projects at film school, guitarist and photographer too. Really good human being as well Just detected your blog: impressive. wishing you continued inspiration and health.

Just detected your blog: impressive. wishing you continued inspiration and health. This is by far amongst the best curated creative content sites out there and the eye and vision of one man, when good, works better than any funded team. Inspired enormously once again :)

This is by far amongst the best curated creative content sites out there and the eye and vision of one man, when good, works better than any funded team. Inspired enormously once again :) Photo gallery

Photo gallery We need more teachers like you :)

We need more teachers like you :) I discover TL of a writer and respected intellectual, with a tolerant, global conscience: @GhoshAmitav – tx @Milindo_Taid

I discover TL of a writer and respected intellectual, with a tolerant, global conscience: @GhoshAmitav – tx @Milindo_Taid OMG its like a painting!! you have taken photography to another level!!!

OMG its like a painting!! you have taken photography to another level!!! Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery love ur pics…they are like those moments which u capture in your mind and wished u had a camera right at that moment to capture it…but u actually do capture them :) beautiful…!!!

love ur pics…they are like those moments which u capture in your mind and wished u had a camera right at that moment to capture it…but u actually do capture them :) beautiful…!!! Grt milindo. eachtime want to check out something good on net…know where to go now!

Grt milindo. eachtime want to check out something good on net…know where to go now! Guitar in your hand reminds me of the MCRC days! You are terrific… :)

Guitar in your hand reminds me of the MCRC days! You are terrific… :) Photo gallery

Photo gallery i really like your blog – good interesting stuff as always !

i really like your blog – good interesting stuff as always ! Its really good to see you Milindo, with such awesome stuff from you as usual.. loved your blog as well!

Its really good to see you Milindo, with such awesome stuff from you as usual.. loved your blog as well! great blog :)

great blog :) You are inimitable!

You are inimitable! Your courses were always the best. By the way, just went through a bit of your website. It’s great! Some good stuff in there that I wouldn’t normally chance upon

Your courses were always the best. By the way, just went through a bit of your website. It’s great! Some good stuff in there that I wouldn’t normally chance upon #NowFollowing @Milindo_Taid One of the most influential n interesting mentor from my design school. Always loaded. :)

#NowFollowing @Milindo_Taid One of the most influential n interesting mentor from my design school. Always loaded. :)